The Computer Architecture

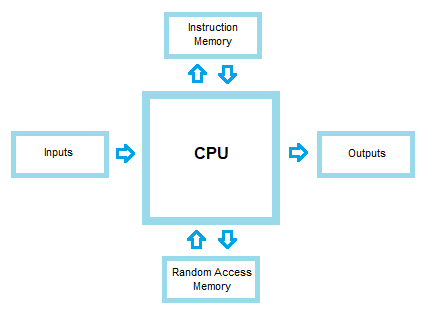

A general purpose computer consists of a Central Processing Unit (CPU), Memory Units, and Input/Output ports.

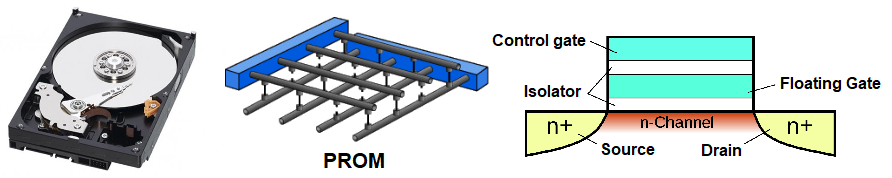

Memory is anything that stores (or remembers) a state. With electronics, it could be a disk filled with microscopic magnets (a hard disk), or a lattice of wires with fuses (PROM), or an array of floating gate transistors (a solid state drive), or a bank of logical circuits (RAM), or anything else that can both store a state, and output a signal based on that state.

When input and output devices, like your keyboard, mouse, and monitor, are plugged in, their memory is assimilated into the computer's memory, which allows the computer to freely modify the memory of those devices, and/or respond to electrical signals from them. By modifying specific bytes in your monitor's memory, it can change the color of pixels. By reading the registers of your keyboard, it can see what keys you pressed, and modify its own memory based on your inputs.

The CPU is a convoluted web of logic gates whose purpose is to process specific electrical signals, and use them to modify its own internal state, and also produce output signals. Within the CPU, there are very small memory units (registers). Because they are so small and close to the CPU, they can be modified at incredible speed, and most instructions do nothing but modify those registers.

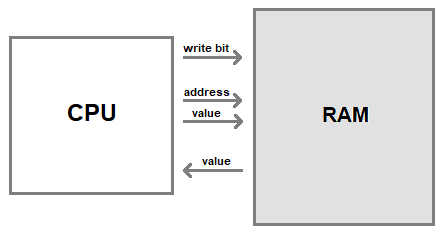

So how does the CPU modify memory? The output signals of the CPU are connected to the inputs of other devices. RAM (Random Access Memory) is a type of memory unit that has three inputs (an address, a value, and a write bit) and one output (a value). Within the RAM, there are millions of tiny 8-bit registers, each containing one byte. There are also millions of multiplexers used to select exactly one of those bytes based on the address input. The RAM always outputs the value of the byte at the inputted address. If the write bit is on, then it will overwrite that byte with the value input. The CPU uses those inputs and outputs to read from/write to the RAM.

The moment a computer is powered on, the CPU receives an instruction from address 0 of the Instruction Memory (which is often read-only memory, or ROM). ROM is very much like RAM, except that it only has one input (an address) and one output (a value). The instruction causes the CPU to modify its own registers and outputs. It could add one register to another, or subtract, multiply, or bitshift. It could move one register to another, it could use logical operations on registers, it could store its registers in RAM, or it could load values from RAM into its registers. In some cases, it could produce a pseudo-random number, or even encrypt data. The possibilities are limited only by the types of instructions that were hard-wired into the CPU. The instruction itself is made up of electrical signals, many of which flip tiny logical switches, and others which get stored in registers.

There is one special register in the CPU called the "program counter". This register can be modified, and is continuously fed back into the ROM to determine which instruction to receive next.

Computability

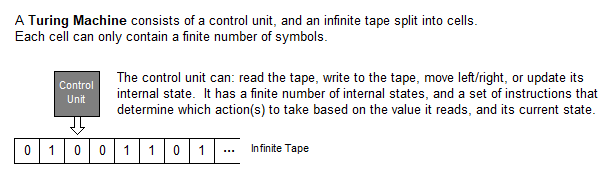

A general purpose computer is a blank canvas. Programming languages are your palettes, and text editors are your brushes.A computation is any process that can be described by a set of unambiguous instructions. In 1936, Alan Turing proved that the set of all things computable can be reduced to the capabilities of a very simple machine, a Turing Machine. No deterministic mechanism can ever surpass the theoretical capabilities of a Turing machine, and conversely, anything that can emulate a Turing machine can perform any computation, given infinite time and memory.

Anything that can be computed can be computed with a Turing Machine

Built into computer chips is a small set of instructions, from which it is possible to execute any computer algorithm. Assembly Languages are the sets of instructions hard-wired into general purpose computer chips. Assembly languages are Turing Complete, meaning they can emulate a Turing machine, and thus can perform any computation using some combination of instructions. Every program run on your computer is first translated into a list of assembly language instructions, then executed. With special programs called debuggers, you can read each program instruction, one at a time, deduce how everything works, and even modify it as you see fit.